The Best American Liturgy

How Contemporary American Poets Are Denaturing the Poem,

Part IX

By JOAN HOULIHAN

"As good a comprehensive overview of contemporary poetry as there can be."

With this qualified, rather doleful tag from Robert Pinsky on the cover and with the basket of “new writing” inside, the anthology called The Best American Poetry continues to be the equivalent of a fruitcake for all the poets on your list: traditional, made by hand, full of unidentifiable nuggets, and largely inedible. Culled, according to its guest editor, Lyn Hejinian, a foremost practitioner of language poetry and other forms of new writing, from an “array of diverse, historically interrelated, and still autonomous literary magazines published in 2003,” the 2004 volume, not surprisingly, showcases a hefty portion of language/avant/post-avant/experimental writing, but it also, surprisingly, comes with a readable prose introduction from Ms. Hejinian. Such an introduction, plain-spoken enough for any critical reader, is welcome. After a year of metaphorical rocks with unintelligible notes affixed to them crashing through my window and with the tire-squeal of the Winter-Wolfe-Skanky-Possum gang still ringing in my ears, I was happy to have a chance to curl up with a hot cup of tea and this respected practitioner's description of what's “best” about such lines as:

Bruce Andrews, “from Dang Me”

And these:

Mark Bibbins, “from Blasted Fields of Clover Bring Harrowing and Regretful Sighs”

I chose these two poems randomly (there are plenty of other examples to wonder at, these two just happen to appear at the beginning of the book). Lyn Hejinian did not

respond to my request for an interview for this piece, so I can only try to guess at the criteria for selection in general. But even comparing these two poems to each other is like comparing two people speaking in tongues: who sounds better?

Whatever else can be said of them, the first-person-anecdotal-narrative-confessional (aka “mainstream”) poems that have been outnumbered in this volume by such writings as the above, can at least be critically sorted (some are clearly better than others, regardless of whether or not they fit a particular editor or critic's “taste”). Basic standards relating to the craft of writing in general, such as non-clichéd phrases, use of momentum and pacing, lack of unintentional ambiguities and other grammatical problems, as well as evidence of an organizing intelligence, a sense of inevitability, a convincing and/or compelling style and voice and so forth are at least available to the reader in, for lack of a better word, the “mainstream” poem. Poetry, as Pound observed rightly, should be at least as well-written as prose. Further, it bears reflection that while Pound could improve Eliot's poems through application of standards of craft, no such improvement can take place for either of the poems I've excerpted, simply because there is no way to discern any purpose or aim.

Alarming, not so much for their lack of meaning as for their critical immunity, such poems are immune not because of any so-called “difficulty,” or because the poem can only be evaluated in a “historical context” devised and/or approved under the terms of one or another literary canon; their critical immunity exists because poetry is the only field where its practitioners can openly claim that their products are not to be evaluated by others in the same field. As with any highly subjective, paranormal enterprise, having an “outsider” try to “see” how their poem works immediately invalidates the results. You get it, or you don't. Thus, only a true believer can “read” a poem from the church of new writing.

Fortunately, I had Hejinian's clear prose to guide me. For enlightenment on her selection process, I returned to her introduction and found this passage:

Since her task as editor of this volume was precisely to “delimit” the “space” of “American poetry in particular” and to answer the questions that “remain open,” by making her selections, I began to fear that Hejinan was indeed making something clear: she was eager to disclaim responsibility for the entire enterprise:

That about covers it—or no, not yet:

If Hejinian's selections were not made “definitively” or according to generally accepted standards of craft in the field of writing, why didn't she simply provide the alternative standards of selection? A few possibilities come to mind:

2. Her standards can only be known by other members of the church of new writing.

3. She doesn't believe in standards because there is no “best”—one poem cannot be better than another.

Whether or not we agree (and I do not) with the idea that all poems are equal, that there is no “bestness” as Hejinian seems to claim, there is still the problem of her having selected any poems at all. By what criteria? If there is no “best,” then every poet is as good as every other poet. Everybody gets a gold star. Why then, isn't this anthology tens of thousands of pages in length?

To be fair, Hejinian admits her reservations about taking on the responsibility for making choices given she doesn't think there is such a thing as “best”:

But, to be fairer (to the reader), wouldn't it have been more ethical for her to turn down the job if that's her belief? It seems to me that if anything is a disqualifying factor for the job of editor of a Best of American Poetry anthology, not believing in the concept of “bestness” is it.

Meanwhile, Lehman, just a few pages away, is operating in another world, a world where his anthology series has a kinship with those of Louis Untermeyer or Oscar Williams, a world where:

And even as Hejinian insists in her introduction, there is no real “best,” Lehman maintains in his that an anthology inevitably represents a selection process of some kind:

Did they read each other's introductions? Or do they just worship in churches too far apart to hear each other?

As the numbers of MFA graduates in poetry increase year after year and the periodicals and presses devoted to its dissemination also increase, we can suppose there is most definitely a “serious general audience” for poetry. But this serious reader's trust in the Best American Poetry of 2004 does not exist, since Hejinian abdicates responsibility for her selections in the most political of ways—by claiming there is no “best,” thus offending no one, except of course, that serious, general audience who expect her to take some responsibility for her selections. The truth is, as Hejinian herself admits, there is no “bestness” in the church of new writing and that's because there can be no “bestness” when there is no means to determine whether or not one poem, or even one line of a poem, is better than another, when the field of poetry itself, built on a tradition of genius, human emotion, and the need to express universal and profound truths through the most powerful and compressed language one is able to wield, is held in so little esteem by Hejinian and her fellow practitioners that they dispense with the craft required to achieve their best, and instead promote a cult-like worship of the idea that everyone and everything is equal, that no poem shall be left behind. As a result, there is no real achievement in this year's

Best American Poetry.

Copyright © 2005, Joan Houlihan

No, dirt aliens: don't waste good mascara, fiber gives you confi-

dence. Spin doctors vs. gravity, do you spandex wooden leg plus spaz

hemp tempi seize the fey crawlspatiality creatures peel off. Barbie pro-

tons slobber the manual seedling wrapped in human skin. Happy puppy

preconscious vouchers don't brownnose your pal's girlfriend, a swagger

unanointed affect in its gob phase. Automated preparation H—a non-

goosing, a midriff melody—stir the rack up…mere child has her

permit.

Stacked circles (rain down) say green it releases nothing. Bundled

wires. Ellsworth Kelly strides from one red iceberg to the next. Each face

projects onto antennae forging a domain expressed as a skewered pod.

Transparency behind a desk elusive plunge. A dissection of thought into

its components the weight of meat up the wrong street the wrong

backdoor. The blazer missed too as the wiry one observed. Someone

slipped him diet Orangina and he went ballistic. The whole staff cray-

oned their names onto the good luck card while unwitting partygoers

waited for the elevator. Mogul and musician separated at birth one

suggested. Hubris. The directions very specific and yet so many stood

idle. She ravished in black. He charmed in lime.

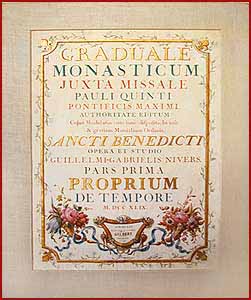

Consider the riddle another way: how do you determine the better, if not best, passage of Greek or Latin when you don't understand the language? Of course, in the case of the Latin Mass, Catholicism found a way to influence millions with a language no one spoke or understood by using other means, distractions both beautiful and bestial. And, as Luther found out, criticizing such an organization led to some nasty reactions. Perhaps there is a parallel, cult-like aura of inviolability protecting this new writing from critical inquiry: such writing, which verges on a kind of liturgy, comes with its own form of worship and its own tenets of faith. True believers do not question its methods; they accept its sacramental texts as the Word. In neither case is readability or critical inquiry at issue. Like artifacts of automatic writing, these liturgical offerings are akin to divine revelation—believe in it or don't, but do not examine, question, or evaluate it. The church of new writing has established what every church needs: their articles of faith. They call theirs “poems.”

The church of new writing has established what every church needs: their articles of faith.

Whither Thou Goest?

Dynamic, ever-changing, poetry (and American poetry in particular) is a site of perpetual transitions and

unpredictable metamorphoses, but there is no end point in poetry. Indeed, American poetry has always

been so full of energy and inventive that it is impossible to define poetry once and for all or to delimit its

space. What is or isn't a poem? What makes something poetic? These questions remain open.

Certainly no single poem in this volume is definitive, nor is any single volume in The Best American Poetry series—not of “bestness,” nor of what's “American, “ nor of “poetry”...

...and if this particular volume is in any way typical, none of the volumes are even definitive of their guest editor's aesthetics or poetics nor even of his or her “tastes....

1. There are no such standards.

Initially I had qualms about taking on the editorship. My problem was simple and, going by what the editors of some of the previous volumes in this series have said in their own introductions, it seems to have vexed many of us. I don't believe in "bestness.”

An anthology aspiring to represent the best work in the field requires faith and trust: the editor's faith that a serious general audience for poetry does exist; the reader's trust in the editor's judgment.

Anthologies are selective; they project an editor's taste, but they are also exercises in criticism. Their job is not only to reflect what is out there but to pick and choose among the possibilities. Whether they set out to reinforce the prevailing taste or to modify it, they sometimes end up doing a bit of both. … All anthologies provide an evaluative function.