|

an ongoing series by Thomas E. Kennedy and Walter Cummins

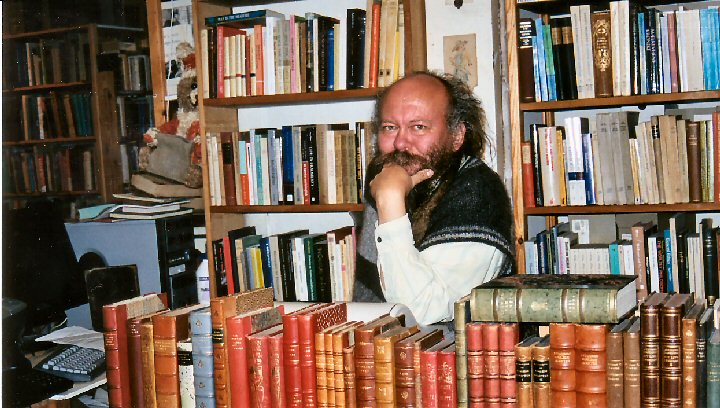

photo by Alice M. Guldbrandsen |

Dostoevski on Skinner Street:

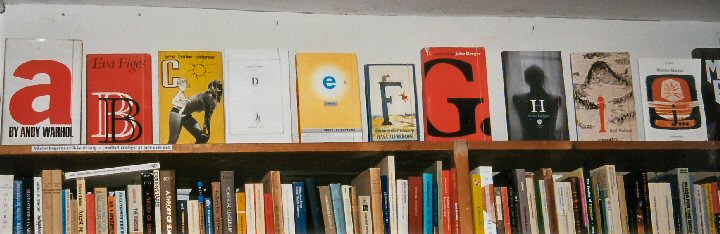

Above his head is a long shelf of books which he spent years collecting. They stand on their lower edges, cover out, and their one-letter titles spell out the alphabet, starting with A by Andy Warhol and running 29 volumes, all the way to the last three letters of the Danish alphabet – Æ, Ø, Å (Ø is the Danish word for “island” and is thus the Danish title of that visionary book by Aldous Huxley from 1962, the year before he died on the day JFK was assassinated.).

Clearly a man who not only sells books, but reads – and writes, edits and publishes – them as well, he explains his wish to assemble this collection of mono-letter titled volumes with a quote from Joyce's Ulysses: “Books you were going to write with letters for titles. Have you read his F? Oh, yes, but I prefer Q. Yes, but W is wonderful. Oh, yes, W.” A customer has also contacted Lars to show him the dictionary he has compiled of one-letter words in many languages – he has collected over a thousand of them. And Lars's Booktrader Publishing has, inter alia, published a dictionary for animals – from which a “gris,” for example (Danish for “pig”), can look up how to say “oink” in twenty-five different languages.

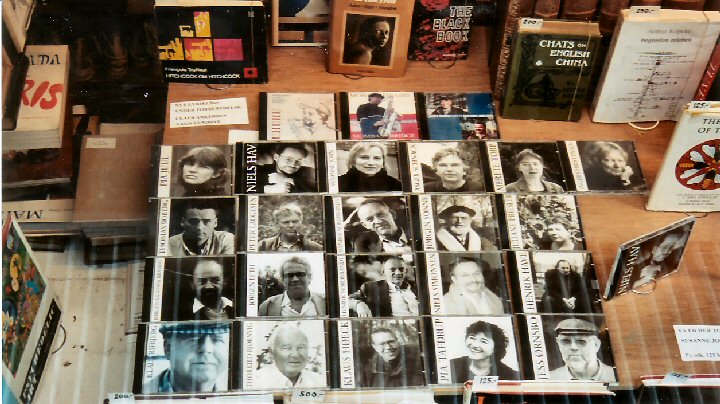

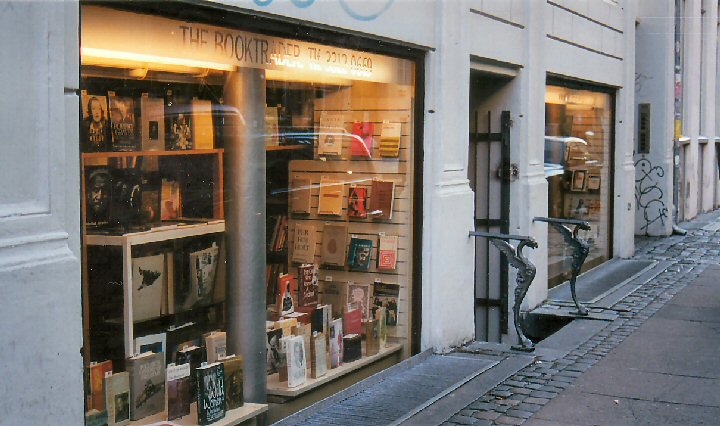

In the broad display windows outside the shop are, inter alia, the remains of an eighty-book collection of Joyceana – down to fifty-seven at this writing – and many another thing, including a gathering of sexy-covered noir paperbacks and the CD poetry reading series Lars published on the Booktrader label – an audio documentation of outstanding turn-of-the-century Danish poets – and jazz CDs. Every year he travels to the Cape Town townships with his wife to hear jazz, and his expertise on South African jazz is documented in several volumes on the topic, published by Booktrader Publishing and also displayed in the long front window.

Behind and around him in the half-basement shop are shelves and tables and shelves and shelves and shelves of books – approximately fifty thousand of them in stock, including the lonely man's table, heaped with used Playboys and Penthouses on sale for $2.50 apiece. All ripe for a honeymoon of the hand.

David Grubb I knew well for a time, and Bodil, too. I met them around 1981. Sick of the relentless rejection to which my fiction had been subjected for too many years, I had decided to quit writing –and to quit reading, too. If I couldn't write, I wouldn't read. If no one wanted my stuff, I didn't want theirs either. Living in Copenhagen, I saw an ad in one of the Danish newspapers placed by someone interested in buying second-hand English-language books, of which I had hundreds. The ad had been placed by David Grubb. He came over to our house and selected about 400 books from my shelves, all fiction – I had it in for fiction, didn't want to sell my poetry. I figured he would give me like a dime apiece, but he offered a dollar. He wanted the books to stock an English-language bookshop he was opening. I didn't think he would do very well as a businessman, paying that much for used paperbacks. He was from Indiana, as near as I could figure a kind of hip Quaker businessman book-lover, a tall bearded man in his early thirties, maybe five years younger than I. We invited him to stay for dinner, and he called Bodil to come join us, and we spent a pleasant evening together.

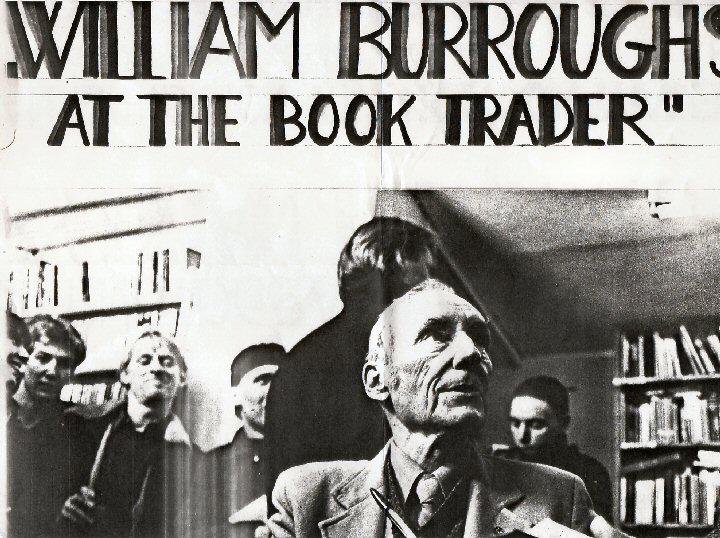

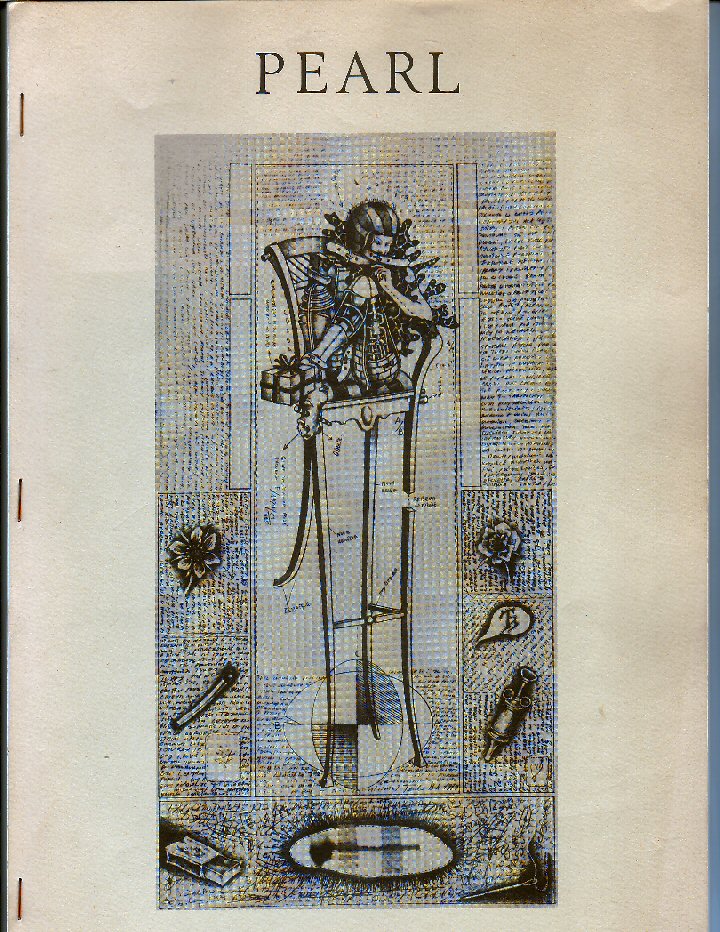

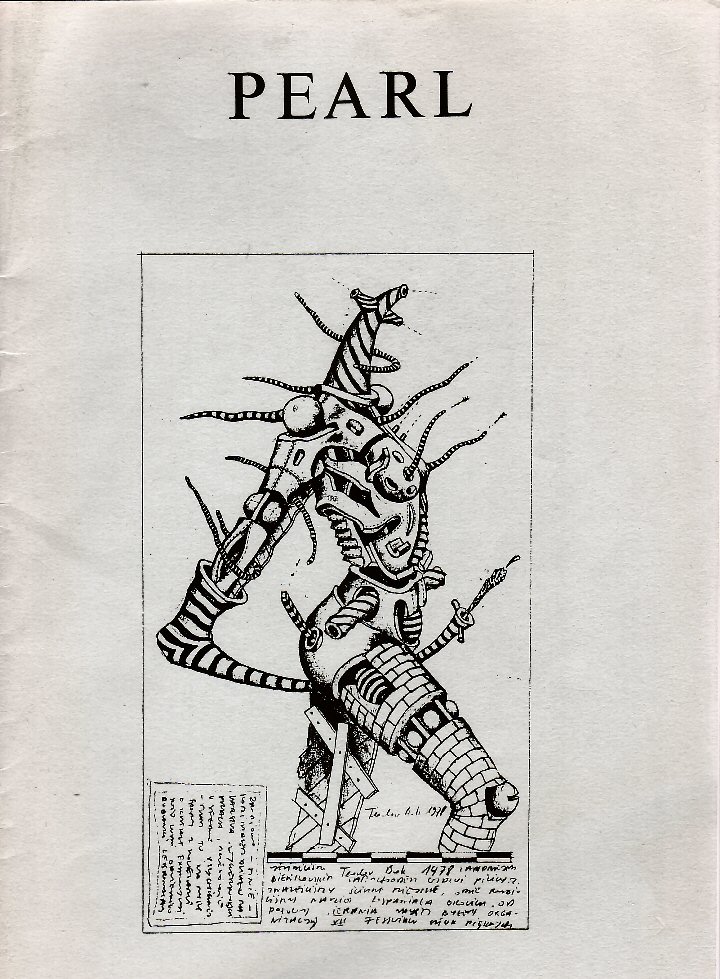

There was a public signing and interview in the shop to launch Burroughs's Cities of the Red Night, followed by a stage appearance at the theater Saltlageret (a former salt warehouse) in which Burroughs read from his work. The film from the interview and reading will be incorporated in a Burroughs retrospective documentary currently under production by Lars Movin. Questions for the interview were also devised by Greg Stephenson, an American expatriate writer in Copenhagen who, with his wife Birgit, herself an expert on Paul Bowles, had been editing the English-language magazine Pearl – a stapled journal of powerful content and with strong, original art on the cover. During the 1990s – at which time publication of Pearl had been taken on by Lars Rasmussen, it was named by the Library Journal as one of the ten best literary magazines in the world. Pearl discontinued publication in the late 90s. The two issues I have in my possession – one from 1982, prior to its Booktrader publication period, one from 1993 – give a fair idea of the quality of content: George Starbuck, John Ciardi, Ferlinghetti, Neal Cassady, Philip O'Connor, Alan Sillitoe, with covers and illustrations by the distinguished Polish-Danish artist, Teodor Bok.

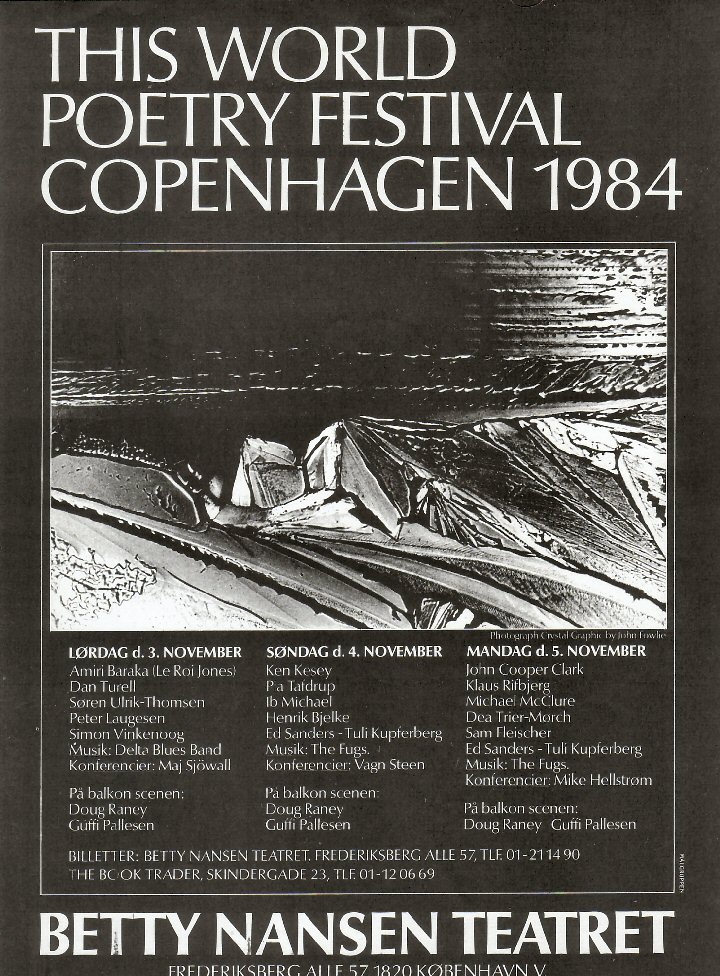

After the Burroughs event, David received a sizeable grant from the Danish Ministry of Culture and founded an organization known as This World Poetry Foundation and invited me to sit on its board. He organized a three-day literary festival in the Betty Nansen Theater with international names like Amiri Baraka, Ken Kesey, Ed Sanders, Michael McClure, and the Fugs as well as many prominent Danish writers – Dan Turèll, Klaus Rifbjerg, Bo Green Jensen, Pia Tafdrup, Ib Michael, and others.

Since then and since Bodil's untimely death at the age of 46 and David's departure to Amsterdam, I have had very infrequent contact with the Booktrader, but today I am on my way to learn about the more recent history of the store and to learn more about Lars Rasmussen. Moving against the stream, I thread through the demonstrators marching along Skindergade toward the Town Hall. I snap a couple of photographs in passing and am rewarded with the devil sign by the young marchers – learning only later that this is the contemporary equivalent of flashing the okay circle of finger and thumb.

Greg Stephenson is the author of several books of literary criticism – studies of J. G. Ballard (Out of the Night and into the Dream), Gregory Corso (Exiled Angel), the beat generation (The Daybreak Boys) and Understanding Robert Stone. When I ask what he is writing now, he answers with his mild voice and expression, which have always seemed to me mildly and blithely ironic, “Nothing. I don't have time to write or to read either – only teach. I've got two part-time jobs at Copenhagen University which take me 11-12 hours a day seven days a week.”

Lars is in Cape Town once a year to hear jazz. He avoids Johannesburg which is very rough, but has never felt threatened in Cape Town or the townships. “In Cape Town you still see white people traveling first class on the trains and black people in third class. Even at some of the beaches that used to be white only, it is rare to see black people. And sometimes a black person will call you 'boss' – from the Dutch 'baas' – but basically those are people trying to sell you something, to flatter you.”

“Perhaps some come with wine also?”

The Booktrader, Skindergade 23, Copenhagen

Essay and Photos by Thomas E. Kennedy

In a subterranean bookshop on Copenhagen's Skindergade, a man standing behind the counter looks as much like Fyodor Dostoevski as any man I have ever seen. His name is Lars Rasmussen, a fifty-year-old Dane.

Lars Rasmussen's alphabet collection of books: “Have you read his F? Oh, yes, but I prefer Q.” (James Joyce, Ulysses)

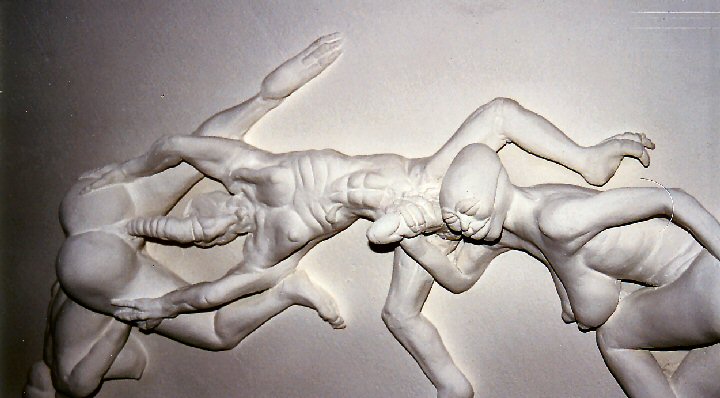

On the other side of Lars, affixed to the ceiling, is an erotic wreath molded in plaster. It depicts a curling strand of figures engaged in various sexual couplings and wafting like a string of pearls out of a molded book at its center. You wouldn't notice it unless you stood directly beneath it and tipped your head back all the way to study the ceiling above you. Lars engaged the artist, Kasper Holten, to sculpt it for him in 1999.

Detail from erotic plaster sculpture from 1999 on ceiling of the Booktrader. Artist: Kasper Holten

Display of Booktrader CDs of contemporary Danish poets

Lars Rasmussen has owned the Booktrader since 1988. The shop originally opened five years prior to that, in 1983, by its founder, the American David Grubb and his Norwegian-Danish partner, Bodil Bødker-Næss. I know Lars hardly at all, but am on my way this mild May day of Copenhagen demonstrations against government cuts in welfare to spend an afternoon interviewing and getting to know him.

Front of The Booktrader on Skindergade with griffin handrails at stairway down to entrance

Two years passed during which time I decided to write one more story, and I knew, I could feel, as it poured out of my pen, that this was my breakthrough. The story, titled “The Sins of Generals,” was accepted by Confrontation magazine in January 1982. I was so startled by the acceptance that I very nearly withdrew the story, under the Groucho Marx principle that any magazine that wanted a story by me was not a magazine I wanted to be in. But I refrained and instead took Beckett's advice: I went on.

Then I received an invitation from David Grubb to the opening of his bookshop, a wide-faced basement shop, three steps down on Skindergade in the center of Copenhagen. Half the shop was a bookstore, the other half a weavery run by Bodil. The shop was handsomely appointed, and I wandered around, wine glass in hand, examining the titles on the shelves. Every fifth book or so had once been mine, and the penciled prices inside the covers showed that David knew more about business than I had imagined. The books he'd bought from me were priced at ten times or more what I got for them. I'd had no idea how scarce literary books in English were in Denmark. Now that I was a published writer, I was ready to begin reading again and to admit volumes of fiction into my home, so I began to buy them back – at a fat mark up!

No matter, it was a good cause. I liked David, and I liked Bodil, and I liked the shop and the weavery, too, and bought a piece of Bodil's textile art depicting a New York street in night blue with silver light, now hanging on the wall of my son's northside apartment. The shop was roomy and bright and there was a conversation pit at the center of it and interesting customers. A literary gathering place had been born.

Soon David brought in William Burroughs, to have him interviewed in his shop by the legendary Danish poet and performer, Dan Turèll, and the younger poet, Sam Fleischer, and people recognized that David was a serious cultural force. That was the only time I ever saw Burroughs. I'd been expecting a wildman, but was startled to find he was a tall, slim, elegant fellow, wearing a sweater vest under his narrow sports jacket, tie knotted to the throat of his button-down collars, his voice crisp and Brahmin clear.

Poster of William Burroughs appearance in the Booktrader in November 1984. Behind and to Burroughs' right is Knud Odde, bass player for the Danish rock group Sort Sol (Black Sun). To Odde's right is the singer. Rasmussen has an extensive collection of never-before shown photos of Burroughs that he will be putting up for sale when he has finished preparing his Burroughs catalogue

Cover of Pearl No. 9, Spring 1982.

Cover of Pearl 14, Winter 1993. Cover art of both is by Teodor Bok

Poster from This World Poetry Festival 1984 where, inter alia, the readers included Ken Kesey, Ed Sanders, Michael McClure, Amiri Baraka and many others

Sidling down the three steps into the shop, I find Lars – despite his Dostoevskian appearance – not a brooding fellow, but a smiling, welcoming host. In no time at all he is filling me in on the shop, its history before him, its history with him, its current history. He is also filling glasses with an excellent Chilean merlot.

I learn that Lars lives in the little north side neighborhood of Brønshøj, near the marshes, with his wife, Birte, who managed the other bookshop (The Magic Flute) he opened in eastern Copenhagen for a few years in the '90s.

Formally educated as an antiquarian, Lars explains that there are those who deal with rare books and those who handle ordinary second hand volumes. He describes himself primarily as the latter, although he does deal in some rare books. When he has something very expensive, he auctions it on line. He tells about the history of the building that houses The Booktrader, built in 1831-32 on the ruins of the old Grey Friar Monastery (Gråbrodrekloster), which was demolished in 1536, during the Reformation. Excavations in the backyard indicate that people, possibly monks, had been buried here during the Middle Ages. Skindergade is one of the oldest streets in Copenhagen, originally housing the city's skin and fur traders. Around 1880 it was host to ten bookstores, four of them dealing exclusively with used books. Today only one other remains on the street in addition to the Booktrader.

Under David Grubb, the store sold only English books. Lars Rasmussen's stock is half Danish, half English, and he deals only in the humanities, specializing in fiction, poetry, history, art, architecture, photography, linguistics, philosophy, psychology, religion, literary criticism and music (jazz, blues and rock). The store also hosts occasional exhibitions of sculpture and art.

Our conversation by the counter is interrupted by customers. One asks if Lars has any Modesty Blaise in stock, and after he has directed her to the relevant shelf, he says to me with a smile, “You won't include that, will you?” A man comes in to ask for books about glass, of which Lars has none at the moment. I learn that books on glass are few and far between. A woman wants something on Chaucer. Lars collects two armloads from different sections of the store and lays them out for her on a stone sculpture that doubles as a display table. After much deliberation and some advice from Lars that she might be able to find precisely what she wants at a shop just up from Nytorv, she leaves without buying a thing. Lars seems undiscouraged, even when the next customer asks in German for a book about clock mechanisms.

Another man enters and requests one of the Joyces in the window. I ask if he is a Joycean, but he seems disinclined to reply. Yet another man steps down the three stairs to talk about the shoddy work that has been done on the cobblestones just outside. Lars tells him he's worried that someone might trip, and the man promises to do something about that as he stands with his head tilted back to admire the erotic sculpture overhead. When he is gone, I ask, “Who was that?”

Lars looks at me. “I don't know.”

At just that moment a man in suit and tie enters and presents Lars with a half quart can of Guinness stout. Lars thanks him and the man wanders off to browse through the shelves.

I recall that David Grubb once told me he had to bring in an average of a thousand crowns a day (about $150) to stay in business.

“It's more like 2½ times that now,” says Lars.

His lease on the shop expired some time ago so he is at the mercy of the landlord who increased his rent last year by forty thousand crowns (about $6,500) and there is an automatic increase of 5% a year.

The door opens again and Greg and Birgit Stephenson appear. After a flurry of hugs, we reminisce about the old days, the three-day festival with the Fugs singing their '60s hit, “I Feel Like a Bowl of Home-made Shit,” and Ken Kesey drinking beer and snorting stuff and making a carny event of bending the bottle caps double between thumb and forefinger. I remember being disappointed at his reading – a two-dimensional portrait of John Lennon, caricatures of good and evil that he seemed to want to believe, a writer whose first two novels in the 60s had revised my mind. But in retrospect, I am immensely grateful to have had the opportunity to meet him, for his good cheer, for the opportunity to hang around with him and Ed Sanders and the others. On that occasion I also had the opportunity to ask Kesey, during a press conference, whether he would be willing to participate in a literary wrestling match with John Irving since both writers had been college wrestling champs. Kesey looked coolly at me and said, “I would drink John Irving like a glass of water.”

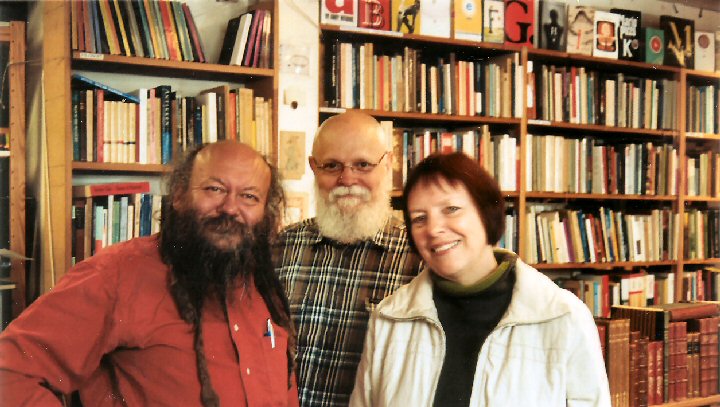

The editors of Pearl (from left): Lars Rasmussen, Gregory Stephenson, Birgit Stephenson. Note alphabet of books above and to the right

We try to remember the names of all the people who used to gravitate around the Booktrader, the group of regulars who would assemble at Charlie's (then Charlie's Wine Room under the original eponymous Charlie, an Englishman who turned a failing bookshop into a thriving public house), but it has been a couple of decades – Martin Benson, the Scottish painter; the late John Fowlie, a British photographer and artist whose ungrounded imprisonment on false drug charges inspired a story of mine called “Danish Light”; Barry De George from Los Angeles, who had been writing a doctoral dissertation at Lund University asserting that the oil crisis of 1973 was a sham (Interpreting Crises) while fighting a legal battle to claim his Italian passport so he could move to Rome. There was an enormous young Dutch guy who had been a paratrooper in the Amazon, a sea captain who had hosted Thanksgiving for the whole group…

Soon Greg and Birgit are on their way, and Lars is popping the cork of another bottle of Chilean. A man who responds to an empty bottle by opening another is my kind of fellow, and the interview plunges on.

I ask if he has plans for more events, readings. Although people are eager for him to do so, he says, there really isn't enough room in the shop. This is why he started the CD series instead. There are twenty-three of them with some of the best living writers in Denmark, perhaps in northern Europe. Poets like Henrik Nordbrandt and Pia Tafdrup, both of whom have won the Nordic Literature Prize over the past few years, the highest honor that can be bestowed on a Scandinavian short of the Nobel; Inger Christensen, highly celebrated in Europe though little known in the English-speaking world. The recently deceased Thorkild Bjørnvig, whose infamous apprenticeship to Karen Blixen (yes – the one played by Meryl Streep) is celebrated in the book The Pact.

As if on cue, a young woman comes down to ask for Inger Christensen's CD. “She has such a wonderful voice,” the girl says, and Lars rings up 125 crowns (about $20).

“Do the CDs support themselves,” I ask.

Matter of factly, he replies, “Not at all. A few of them have sold about ten copies.”

“Do you give a discount if someone buys all twenty-three.”

“It could happen.”

Another customer enters, bearing a satchel. Lars glances at him and says, ”See what I have.” Clearly he knows the man's passion. Lars disappears into a side room and re-emerges with a large, hard-bound book that he lays open, flat, on the center table. It is an 1850 edition of a German toy catalogue. The man leafs slowly through the book. “These illustrations are hand-painted,” he murmurs. “I don't even dare ask the price.” Lars explains that you can date the catalogue by looking at the illustration of the toy steam engine, an early model, and they get to discussing the dating of books. From a folder in his satchel, his customer takes out a large sheet of paper on which are printed all the varieties of the Penguin logo from its first appearance until now – there are penguins at attention, dancing penguins, hopping penguins, waddling penguins. Lars agrees to print the sheet with some commentary by the customer in his next Christmas Album.

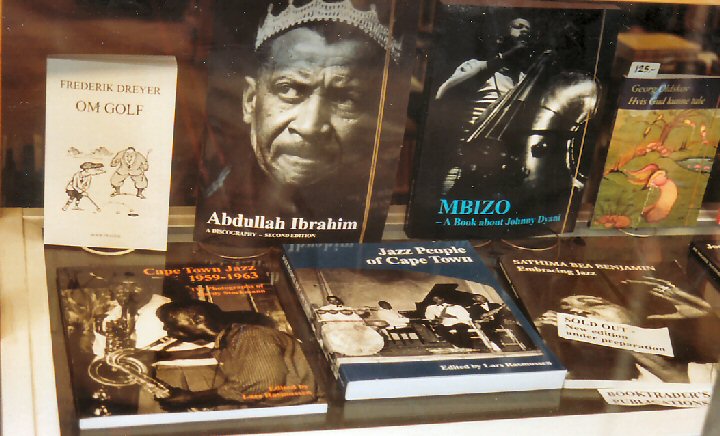

Among the books Lars has published are one about the German artist, George Grosz, a couple of his own collections of whimsical erotic stories under a pseudonym (he has also written several hundred pages of short stories for which he is seeking an American publisher), a few books about South African jazz, even one about golf because one of his daily customers is a golfer.

“Do you play golf yourself?”

“Not at all. It would bore me to death. But this golfer architect came in every day, and I got the idea to publish his articles, and we sold the whole edition of 800 copies. That was our only success. The jazz books had their initial inspiration because in the '60s and '70s a lot of African jazz musicians started coming to Copenhagen to get away from the apartheid. At that time, we didn't really have racism. That came later. They played at Montmartre, and that's where I first heard them and was so attracted I started collecting their records. The first book I did on this was a discography of Dollar Brand or Abdullah Ibrahim as he is now known – a huge book – and that led to a book about his wife, the singer, Bea Benjamin. Then I stumbled over an amazing collection of historical photographs of jazz musicians from Cape Town from the 60s taken by a German guy named Hardy Stockmann. I traced him to Bangkok and bought his whole collection of pictures and published it. After the sixth book, I had to stop. The financial side of it was terrible – big books with pictures, very expensive, and they don't sell much. But making them was fun. There is still a stock available.” br>

Display of Booktrader publications on South African jazz and golf.

br>

Display of Booktrader publications on South African jazz and golf.

“Do you play golf yourself, Lars?” “Not at all. It would bore me to death.”

“But the jazz clubs are good?”

“There are a few jazz clubs in Cape Town. They come and go, but I especially like to hear the old guys play. Local style Cape Town jazz influenced by a lot of things, tribal music, but also an interesting influence from Malay music because there is a Malaysian population in Cape Town who were brought there as slaves, and they have their own music which has influenced the jazz. So Cape Town jazz is unique. I got to meet a lot of people because I was never afraid to go into the townships – a lot of white people are afraid to go there – but I never had any trouble at all. I take a lot of pictures of those guys, too.”

He also visits New York every year and stays at a hotel on 17th between Fifth and Sixth Avenues called the Chelsea Inn (no relation to the Chelsea Hotel), a small place run by very nice people where, he says, you can get a nice double for about $140.

Another of Lars's specialties is the beat generation. He is currently preparing a Burroughs catalogue, has a good collection of Burroughs photos that have never been shown before anywhere, and they will be for sale. He also has many books by the beats. He has built up his stock in the shop from scratch; when David moved out the shop was empty. He had sold every last book.

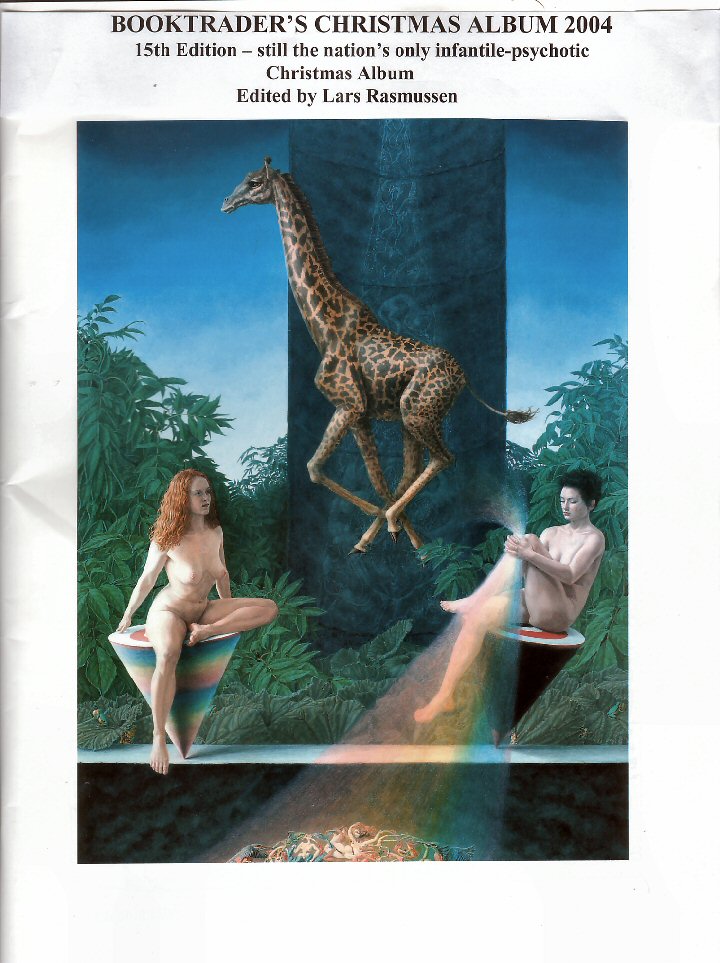

One thing that he does continue to publish is his annual Christmas Album – a collection of writing and art solicited from his customers, some of whom are professionals, others amateurs. He has been publishing this annually since 1990, except for three years when he didn't have the money. He sees it as a kaleidoscope of styles and sensibilities, and he gives the magazine away free, with ten copies for each contributor. It is published on December 3rd every year, the birthday of the classic Danish writer, Ludvig Holberg, whose seated sculpture sits outside the Royal Theater on the King's New Square. People come in to the shop that day to pick up their copies. “We have a lot of fun that day,” Lars says.

Booktrader Christmas Album – a collection of writing and art edited by Lars Rasmussen and solicited from his customers, some of whom are professionals, others amateurs, a kaleidoscope of styles and sensibilities. The magazine is published on December 3rd every year, the birthday of the classic Danish writer, Ludvig Holberg. People come in to the shop that day to pick up copies, free for the asking. “We have a lot of fun that day,” Lars says. Cover art is by Rigge Gorm Holten

“It happens,” he says. “If I get a bit drunk I can tell you stories. Now that we're starting to talk about that, they're coming back to me. Next time you're here, I'll tell you some stories.” But he goes on now anyway.

In the first half of the 90s, he tells me, his shop became a wild place. When he opened at eleven, people showed up with beer and wine and would have a couple of drinks. They would leave and then the next group would come in and then the next. But Lars was there with each group, drinking all day until he closed – as many as twenty bottles of beer a day. It was great fun and very exciting. People were drinking, smoking, fucking in the back room. Books fell onto the floor. People would dance on them. Books were thrown out the door onto Skinner Street. People laughed and cheered and opened fresh beers. There was a woman who when she came in sometimes would remove her blouse and walk around topless as long as she was there. Lars and his wife had separated, and he was often sleeping in the back of the shop, on the floor, no mattress.

“It was great.”

He was in his forties. Everyone who came in for the daily party was free to leave at will, but he was a captive guest. Not that he didn't like it. He liked it. The guests were fun and interesting and many of them were famous as well. But at one point he realized that he was killing himself.

Finally one day he put up a no smoking sign. That cut the size of the daily party in half. Then he cut down drastically on his own drinking. People had begun to see him as the host, the joyous host, and when he was no longer throwing them back, the party began slowly to wind down. Then he had his life back again, and happily, he and his wife got back together again. But he never regretted those times. He thinks back on them even today with pleasure and nostalgia.

“You should have been here, Tom,” he says, and I wish I had been, wish I had known.

Today, he and his wife live a stone's throw from their daughter and two grandchildren in a house they bought in the mid-1980s in the Brønshøj section, just north of Copenhagen. It occurs to me that in 2008, the Booktrader will have been in function for twenty-five years, and Lars will have been the proprietor for twenty of those years.

“That's a big event,” I say. “You ought to do something to celebrate.”

“Yes,” he says, “Maybe I should burn the place down.”

“Really,” I say. “You should do something. We could fly David Grubb in for the event.”

“Maybe,” he says. “We'll see.”

“Really. You should. I'll chip in for his ticket.”

“Maybe so,” he says. “Sure, why not, we could do that.” He smiles enigmatically at me. “Maybe so.”