|

|

The Literary Traveler

|

an ongoing series by Thomas E. Kennedy and Walter Cummins

|

|

TOMBA EMMANUELLE:

THE LEGACY OF THE 'LESSER' VIGELAND

AND THE NORWEGIAN MODERNISTS

Photos and Commentary

by Thomas E. Kennedy

At last I have found it.

Nearly two decades ago, at an international party in a turn of the century mansion in Copenhagen, past midnight, in the dim light of the ballroom, a beautiful young Norwegian woman told me about a little-known collection of Gustav Vigeland's erotic sculpture which required special permission to access. A pleasantly flirtatious thing to discuss while dancing. I was as taken by the fact of the collection as by her obvious relish in telling me about it. After the dance, I never saw her again and don't even remember her name, but I remember the light, the music, the glint in her blue eye and on her smiling teeth as she told me about it. I remember a Portuguese fellow dancing beside us, thrusting his arms into the air and pronouncing with elation, “Eet ees a good Astra thees night!”

Resolved to find and be admitted to that collection, I made a few enquiries amongst Danish and Norwegian acquaintances, but nobody seemed to have heard of it, not even my American novelist friend, Susan Schwartz Senstad, who has been living and working in Oslo for years and knows a great deal about the city and its art. Was the young Norwegian woman pulling my leg?

I put it aside but didn't forget, thinking one day I would take the time to research this seriously. From time to time I would meet a Norwegian at some function and ask about it if the situation lent itself to such enquiry—it is not always appropriate to fall upon a new acquaintance with questions about erotic art.

Then one day not long ago the obvious occurred to me; I asked Hans Asbjørn Holm, a Norwegian physician I've known for years and run into every few months.

“I know it vell,” he told me. “In fact I live nearly next door to it, in the Slemdal area of Oslo, a little bit out of the vay. But it is not Gustav's art. It is his brother Emanuel. And the museum is very special and only open for three hours each week, on Sundays, from noon until three.”

This was sixteen years after the young Norwegian woman's glinting eye had planted the seed of curiosity in my mind. So I bought a ticket on the Oslo Ferry, sailed from Copenhagen one Saturday evening, up through Kattegat and Skagerrak toward the Oslo fjord. After dinner, I sat in the ship's disco watching the dancers being tossed around the floor by the pitching sea, wondering if the collection would really be worth this time and expense.

|

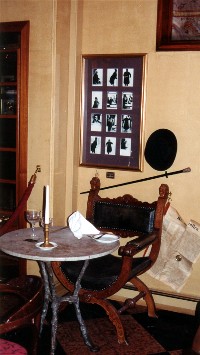

We docked in Oslo at nine in the morning, too early. The museum—called Tomba Emmanuelle—would not open for three hours. So I took my breakfast in the Grand Café at Karl Johannes gate 31. Like the Theater Café at Stortingsgatan 24-26, the Grand is steeped in literary history. I sat across from the table that for decades was permanently set for the great Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906) with his stick, hat and spectacles hung behind the chair, napkin and wine glasses before it. (Alas, the table has since been “temporarily” dismantled in connection with a remodelling of the café, although a staff member has assures me it will be resurrected.)

|

|

Then I was in a taxi headed north for Slemdal and twenty minutes later climbing out at Grimelundsveien 8 before what appeared to be a windowless church, red brick, but instead of a crucifix at its peak, there stood a golden angel, wings spread, arms uplifted, gleaming in the sunlight.

This, at last, was it: The Tomba Emannuelle.

But first a little background.

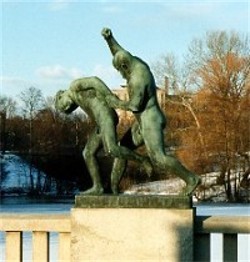

Probably most people who have visited Oslo have also visited the sculpture promenade created by Gustav Vigeland (1869-1943)

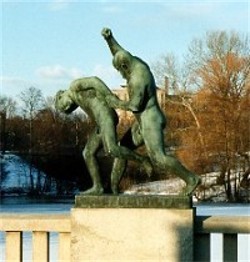

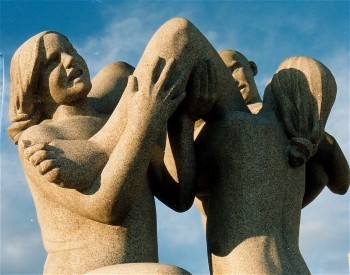

in Frogner Park—

an awesome collection of 192 sculptures portraying more than 600 figures, all modelled in full size by Gustav without the assistance of pupils or other artists. The sculptures are of naked men, women, and children at all phases of life, expressing joy, anger, passion, rage, tantrum, affection, love.

|

|

Birth, procreation, death. They sit atop the railing of a bridge across the Frogner dams that span the park, and they surround the enormous pedestal on the other side.

Certainly the figures are passionate and vital, life-affirming, but with one or two exceptions, I would not call them erotic in the sense, say, that a Rodin or a Manet or a Picasso or a Modigiani or for that matter a Botticelli can be erotic. Although Gustav, too, has created more directly erotic sculptures, those in the Park are more energetic than erotic, wholesomely naked and natural, not evoking a sense of passion or desire.

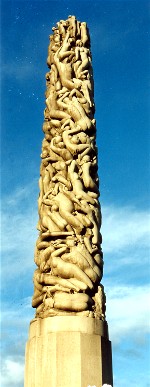

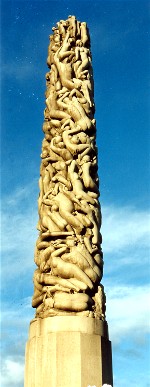

Gustav also designed the architectural setting and layout of the park over a period of 36 years, completing his work in 1943, the year of his death, when the park's centerpiece, the monolith, was set in place (during the German Nazi occupation).

|

The monolith is a 14.12 meter (46-foot) pillar carved of a single block of stone and consisting of 121 naked figures coiling together toward the top, starting with adult figures at the bottom and mounting towards infants at the top. To complete the design of Vigeland's plan for the monolith alone took three stone cutters from 1929 to 1943. It is a massive symbol of the struggle for existence, resurrection, the yearning for higher spaces, the cyclical nature of life. The last of the 58 sculptures across the bridge and around the pillar is The Wheel of Life, figures swirling in an eternal circle. The central monolith stands on a broad pedestal mounted on each side by stone steps and enclosed by sculpted wrought-iron fencing whose silohuetted figures are visible against the sky.

|

Gustav Vigeland is one of Norway's greatest sons, ranked along with Ibsen (a powerful bust of whom Vigeland also sculpted and whose larger than life statue stands outside the National Theater just off Karl Johannes Gate),

novelist Knut Hamsun (one of the fathers of northern European modernism, who won the Nobel Prize in 1920, but whose reputation is marred by his perhaps naïve contact with Hitler in the last part of his life [cf. The Trial of Knut Hamsun by Thorkild Hansen, 1978, and the 1990s Scandinavian film, Hamsun, starring Max Von Sydow]—Hamsun's bust was also sculpted by Vigeland), painter Edvard Munch (1863-1944) and composer Edvard Grieg (1843-1907).

These are amongst the greatest of northern Europe's modernists. What could be more modern, for example, than Ibsen's The Doll House , a case study for the birth of contemporary feminism, or An Enemy of the People, an early portrait of the cynical, self-serving “interests” commercializing and destroying the earth's natural environment? These are amongst the greatest of northern Europe's modernists. What could be more modern, for example, than Ibsen's The Doll House , a case study for the birth of contemporary feminism, or An Enemy of the People, an early portrait of the cynical, self-serving “interests” commercializing and destroying the earth's natural environment?

|

|

Knut Hamsun's novel Sult (Hunger) is another modern amazement, about a young artist starving in the streets of Oslo. It is a rare Norwegian who cannot recite its opening sentence: “Der var i den Tid jeg gik omkring og sulted I Kristiania, denne forunderlige By, som ingen forlader, før han har faaet Mærker af den.” (”It was in those days I wandered starving in Kristiania [earlier name of the city of Oslo], that strange and wonderful city no one leaves until its mark is set upon him.”) In 1881-2, Hamsun lived the life of poverty, cold and hunger he later re-imagined for his novel in Oslo's Vaterland slum -- which has since been cleared, the Radison SAS Plaza Hotel now stands on the streets where Hamsun's desperate narrator wandered—although it is said Hamsun also incorporated the “mark” of winter 1886-7 in Chicago into the portrait. Critics Jan Naerup and Jan Kjaerstad note that the first 30-page fragment of Hunger, published in November 1888 in the Danish literary journal New Earth (Ny Jord), created a sensation that laid the foundation for a new literature in Scandinavia and lifted Norwegian letters to world level. Hamsun, Kjærstad writes, “anticipated and inspired a whole generation of modernists … was read and admired by Thomas Mann, Ernest Hemingway, Franz Kafka, and Andre Gide” among others. Hunger has also been adapted as an extraordinary film (1966) directed by the Dane, Henning Carlsen, starring the Swedish actor Per Oscarsson, who is said to have starved himself for days to get into the spirit of the narrator. One warmly agrees with the New Yorker critic, Penelope Gilliatt: “Oscarsson's performance is phenomenal. The experience of the film is the experience of being this character—in all his fury, antic courage, stoic humor, and suppressed wild exhileration.”

The influence of Edvard Munch on modern painting is, of course, legendary—his quintessentially modern The Scream has become so familiar as to be marketted, alas, as refrigerator magnet, plastic desk cube, ballpoint pen logo, and dwarf-size blow-up sculpture. Munch was also a diligent writer. His Notes of a Genius is redolent of Kierkegaard, Dostoevski, and Hamsun, and he also produced sketches for Baudelaire's Flowers of Evil.

Less well known is the work of the other Vigeland—Emanuel—Gustav Vigeland's younger brother,who has also left behind an impressive body of work. The greatest of these, Tomba Emmanuelle, is as wondrous in its own fashion as Gustav's sculpture park, similar in inspiration, yet unique, unequalled, a museum of such rare unity that it achieves a single, intense effect upon the visitor's senses—not merely the eyes, but the ears, and the very touch of the air it encloses.

The Vigelands—like Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), one of their prime mentors, as well as a mentor to the masterful Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926), who served as Rodin's secretary —were pioneer modernist sculptors who preceded the radical elimination of subject that characterizes what now might be called the most mainstream art and sculpture of the latter half of the 20th century. Ironically, perhaps the seeming accessibility of their art repels that contemporary viewer who wishes art to be as disconnected from the “real” world as music, to be “about” nothing so much as itself, to be non-cerebral, non-intellectual, to comprise color, sound, content that is pure form and the impressionistic interiors of the soul rather than to represent identifiable objects in the world. No comparable movement in literary art has ever taken center focus to the extent it has in the visual; perhaps the closest parallel would be James Joyce's Finnegans Wake, although even there much that is representational can be decoded and deciphered form the text.

Both Vigelands visited Paris in the 1890s and studied the work of the non-academic Rodin who turned from classicism to celebrate incompletion and fragmentation. “And the cathedrals, are they finished?” Rodin demanded, in response to a challenge about his never completed masterpiece The Gates of Hell, a pioneer work of assemblage. Those who view Rodin's The Thinker (or The Contemplator) as a kind of joke, a suitable illustration for a laxative commercial, and his The Kiss as sentimental, might as well complain about Shakespeare's penchant for cliché. In fact, The Thinker first appeared on the tympanium of The Gates of Hell, Rodin's representation of Dante contemplating the sufferings of those in hell, and The Kiss, a representation of the pleasure of man and woman together on earth, originally intended as one of the figures of that massive assemblage, was removed by the artist because it clashed with the spirit of the composition. The side frames of the gates, acrawl with naked figures, sculpted in the 1890s, would seem clear inspirations for Gustav Vigeland's pillar as well as the art discussed below by his younger brother, Emanuel, as Rodin's themes of intimacy between men and women influenced both brothers.

What might seem simple representational works to some viewers today actually came into being during the last decade of the 19th century when modernism was defining and being defined by the European consciousness: In Denmark in 1888, the Norwegian Knut Hamsun was publishing the first fragment of his modernist masterpiece Hunger; in Ireland in 1899, the 17-year-old James Joyce (1882-1941) taught himself Norwegian in order to read the work of Henrik Ibsen—Joyce's first publication was a review in 1900 of the 71-year-old Ibsen's last play, When We Dead Awaken:

We only see what we have missed

When we dead awaken.

And what do we see?

We see that we have never lived.

In France in 1895, the 51-year-old Paul Verlaine, a year before his death in his Parisian apartment at 39 rue Descartes (where Hemingway would live in the 1920s) , was writing the preface for the first collected poems of Arthur Rimbaud, who had died four years before at the age of 37.

In 1892, Gustav Vigeland was studying with Rodin in Paris, and in 1900 Emanuel visited Paris as well. Neither brother had a life of ease. Gustav describes a period of poverty much like the narrator's in Hamsun's Hunger. Their father, a successful merchant who lost his faith at the age of 51 and turned to drink, was given to acts such as ripping the blankets off his sleeping sons on Good Friday to wake them with a whip, exclaiming that on such a day one should suffer!

In 1902—the year after Gustav designed the Nobel prize medal and Emanuel painted his sriking Vita, which shows a healthy baby, head and upper body awash in red sunlight, seated on a dusky decomposed adult corpse -- the Vigeland brothers parted ways, apparently when Gustav suggested how greatly Emanuel's art was influenced by his own.

Emanuel continued to produce murals, frescoes, chalk paintings, stained glass (the 33 windows of Stockholm's Oscars Church, Århus and Lund cathedrals, and Copenhagen's Town Hall). In 1926, he built a brick church-like structure, 10 x 22 meters, with a vaulted ceiling 12 meters high. The windows would later be bricked in. From 1927 to 1947, he employed the walls and ceilings as black canvases, painting figures against a dark, smokey background, preparing the structure as his own tomb.

And now, at last, I am here.

|

Two bright-faced young Norwegian women, students, greet me in the foyer where I pay and approach the bronze port, adorned with a silohuetted frieze of kneeling naked figures of a man and woman, pressed flush together to the waist, arms joined above their heads to lift an infant to the stone lintel. Above the lintel, cut in stone, are the words, Quicquid Deus creavit purum est. All that God has created is pure.

|

The doorway is low and narrow. I tug open the port and stoop to enter, a forced bowing of the head beneath the egg-shaped urn containing Emanuel's ashes. As I rise again and look, my gasp echoes and resonates beneath the high vaulted ceiling as I behold what even 16 years of expectation has not prepared me for.

Tall black windowless walls, more than 800 square meters of fresco, an enormous chamber of art that envelopes the spectator, fills the eye, the ear, all the senses of mind and spirit. It is like entering a dream. A whisper becomes a muffling, enveloping echo. From the dim corners, nearly indiscernible in the smokey light, sculptures peer out at you or draw your gaze.

|

It is like a huge capsule of existence itself, the universe, dark and light, life and death, the struggle to conceive, to give birth, to be born, the inevitability of death and the resurrection from death of new life. The great

themes that occupied Emanuel Vigeland's formidable strength and talent and vision have found expression here in overpowering form, occupying this place, its every detail, right from the door handles to the vent screens, the egg-shaped urn that houses his ashes beneath a fresco of copulating skeletons from which rise a monolith, painted on the wall, of naked bodies reaching to the vault of the ceiling, up to the cupola.

|

|

If you so much as cough, the sound fills the room and becomes an enormous, religious murmur, Coltrane's ghostly chant of Love Supreme, surrounding, engulfing you. Your eyes grow accustomed to the dark, discern bronze figures in one corner, locked in an embrace that defies gravity, a woman and infant in another. The paintings are on the black surfaces of the walls and ceiling themselves: A powerful naked man rising from the darkness into an orb of light, babies held aloft in each hand beneath a darker ceiling of shadowy naked women, children, fleshy thighs, arms, strong backs, billowing serpents, corpses, skeletons.

|

|

|

A nubile, naked woman in a luminous sphere of children, an infant pressed to the top of her head, naked strong children clamoring up her legs as toward birth, their feet upon the back of a pale, dying woman collapsing on all fours, herself mounted on an eerie silver fundament of skulls. A man and woman, loins joined, reclining on a bed of skulls, a luminous skeleton lifting ghostlike from their embrace, a crying baby grasped in its long bony fingers.

Amidst the ghostly reverent, reverbrating whispers of your own movements, the echoing rustles of your clothing, you wander slowly, entranced, back to where you began—

|

the wall above the obverse of the entrance, the urn, the pillar rising from coupling skeletons, sculptures of death, life, a woman with a skull between her parted thighs, frescoes of strong vital limbs…

If this is the shadow of Emanuel's brother's park, it is a shadow of vital substance, no mere celebration of life, but a celebration of life and death, the eternal, mysterious, inevitable embrace.

Humbled and awed more powerfully than by an church I have ever visited, I bow my head again beneath the lintel, step out into the sunlight on Grimelunds Way. Sixteen years of expectation has in no way dampened the effect of what awaited me.

My taxi is waiting. I climb in and ask the driver to take me back to the harbor, exhilerated and uneasy, somehow changed, increased, nourished by the vision of the self-created tomb on which a great artist spent his life.

Bibliography

Emanuel Vigeland (1875-1948), Vigeland-Museet, 1999, 55 pages (Norwegian text with color and black-and-white illustrations), ISBN 82-91830-04-5

The website for the Emanuel Vigeland Museum offers more information, more photos, and an extended bibliography.

[copyright 2003, Thomas E. Kennedy]

|

![]()