|

|

|

an ongoing series by Thomas E. Kennedy and Walter Cummins

|

|

Tinker Bell and Every Imaginable Comfort: Prague Post Kafka

Essay and photos by Walter Cummins

I don't know the source of the misinformation, but Alison – like her mother before her – and I had for years – long before we met each other – believed Walt Disney was Czech-born and that he had emigrated to the U.S. as a child. He was, in fact, born December 5, 1901 in Chicago, son of an Irish-Canadian father and German-American mother. But I didn't learn that until a few weeks ago. Last summer we had visited Prague unenlightened. From the day we arrived and saw the twin spires of the Tyn church behind the Old Town square, we kept finding influences on Disney at every turn, sources of cartoon worlds in the architecture of his heritage. While my intention in the city was to seek auras of Kafka – where he had lived and worked, where he was buried – I kept blurring Franz with Walt; in fact, getting a stronger sense of a Disney reality than of the dark settings that haunted Joseph K.

It turns out my confusion isn't unique. A web site called futurecasts.com notes: “Prague is a thoroughly charming city, with pervasive idiosyncratic architectural flourishes added to the facades and roofs. These make it look like a set from a Walt Disney animated film. Tinker Bell might have flown in over the rooftops at any minute.”

Some lament the transformation of a city miraculously untouched by the two world wars and Russian tanks into a 21st-century tourist haven. The

|

Tyn Church

|

chief European correspondent of Washington Times, Gareth Harding, in an article called “Prague Blighted By Tacky Tourism,” wrote: “The city has also become more of a fun place to live and visit as hundreds of bars, restaurants and night-clubs have sprouted up and opening hours have been extended. The flipside is that the center of Prague has lost much of the atmosphere which once made it unique. The smoky bars serving up plates of gristly meat and dumplings are gradually being replaced by brighter, trendier, pricier, places offering pasta, pizza and pitas. The street markets selling wild mushrooms and garden-produced vegetables have been turned into tourist stalls hawking mass-produced souvenirs. Even the recently-opened Museum of Communism is nestled between a McDonald's burger joint and an Austrian-owned casino. If ever there was a symbol of Prague on the eve of the Czech Republic's entry into the European Union, this is it.”

Despite Harding's upset, today's Prague is a very pleasant place – attractive, charming, inviting – even with the packs of tourists that cross the Charles Bridge and huff up the steep steps to Hradny Castle. (Like the castle described in Kafka's novel of that title, “It was neither an old stronghold nor a new mansion, but a rambling pile consisting of innumerable small buildings closely packed together and of one or two storeys; if K. had not known that it was a castle he might have taken it for a little town” – Muir translation).

Castle buildings overlooking the city, St. Vitus Cathedral within

The Old Town Square is spacious and open, al fresco dining tables lining two sides, clusters of camera-ready people waiting for the clock in the tower of the old town hall to chime while mechanical figures perform their centuries-old ritual. Yes, the city is Disney-fied – spruced up, sandblasted, repainted, an architectural museum, a destination of eager tourists from throughout Europe and the world.

|

|

Kafka created a make-believe Amerika in his novel of that name, but it's the least read of his works and his vision has no legacy. Disney, on the other hand, can be considered responsible for transforming much of the American imagination with his movies and his theme parks, the fantasy land that serves as America's substitute for a mythology, his Mickey Mouse the country's most famous icon. For readers, Kafka's most likely icon is the insect incarnation of Gregor Samsa. But Gregor's Prague no longer exists.

Kafka wouldn't recognize it, beyond the shapes of certain familiar buildings. The city depicted in The Trial is claustrophobic — tiny rooms with low ceilings, narrow streets, strangers peering in windows. Oppressive and menacing. Today's Prague is hospitable, filled with art, music – opera, string quarters, jazz – food, pilsner, boat rides on the Vltava, a fringe arts festival, shopping streets rich with luxuries for the wealthy. No wonder people flock there.

Old Town Square

One symbol of the transformation from the Samsa reality to the new Prague can be seen in the location of the InterContinental Hotel at 43/5 Námestí Curieových, the exact site of the building where Kafka in a third-floor room wrote “Metamorphosis.” Instead of Gregor's broken family, reduced to sharing their small space with lodgers, affluent tourists luxuriate in plush rooms and dine elegantly in a rooftop restaurant. According to its web site, “The InterContinental´s 372 guestrooms, including 89 Suites, have all been recently renovated and feature every imaginable comfort. The hotel offers spacious health club with unique swimming pool, sauna, Jacuzzi, gym and massage facilities as well as most modern golf simulator.” Imagine the look on the face of any guest who opened a door and encountered a man-sized bug halfway up a wall, an embedded apple festering in its back.

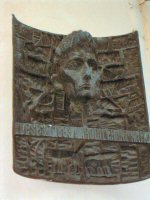

It's not that Prague wishes to secrete the memory of Kafka like a shameful son left to die in a sealed room, a “thing” gotten rid of by a grinning charwoman. Instead, like Gregor's sister, Grete, who with “increasing vivacity . . . bloomed into a pretty girl,” the city has allowed Kafka's legacy to flourish. In fact, it flaunts him. There is a Kafka Café, a Kafka book store, Kafka tee shirts , a plaque on the site of his birthplace at U Radnice 5, even a discrete sign directing visitors to his grave in the New Jewish Cemetery.

|

Czech artist Jaroslav Rona's 12-foot-high bronze statue – Kafka sitting on the shoulders of a headless figure – rises in a tiny park between the Spanish Synagogue and the Church of the Holy Spirit. The building that replaced the birthplace serves as a Kafka museum. As explained by David Sturm, who compiled the route of a Kafka walking tour, “Paying the 20-crown entrance fee (about 50 cents) you can view permanent exhibits including photos of Kafka and his family,

|

|

artifacts of Jewish life in Prague, a map of Kafka-related sites and a timeline of his life. Most interesting is a display of first editions, including a 1916 edition of Metamorphosis, one of the few of his books published in his lifetime. A counter in the museum will sell you books on Kafka, a bust of his head or coffee mug on which the writer's gaunt face stares intently back at you.”

Kafka Museum on the Site of His Birthplace

Kafka Museum on the Site of His Birthplace

While not following Sturm's suggested route, with a list of addresses and a city map, we managed to get to all the Kafka sites over several days. The building that housed the Worker's Accident Insurance Company of the Kingdom of Bohemia at Na Porici 7, where he worked from 1908 to 1922, is now the Hotel Mercure. For a time he lived with his sister Ottla in the small cottage at 22 Golden Lane on the grounds of the Castle, not far from St. Vitus Cathedral. That's now one of a row of shops that require a ticket to visit, another Kafka café at 23. He also had rooms just a few buildings away from the astronomical clock near the Old Town Square. When Franz was a child the family lived on Celetna, only steps from the square, at both numbers 2 and 3, the latter for almost a decade. Franz's father, Hermann, the addressee of the famous unmailed letter, ran a fancy goods shop on the lower level of number 3. When we saw it, number 2 was undergoing renovation, a chute projecting into the street, its barracaded front plastered with advertising posters. When one includes Franz's schools and the various apartments of the peripatetic family, the Old Town is chock full of places that could bear the sign “Kafka slept here.”

Celenta 2

Celenta 2

|

Celenta 3

Celenta 3 |

We even chanced upon an English-language Black Moon Theatre Company dramatization of “Metamorphosis” in a – for us – hard to find theatre on an obscure street of the Mala Strana district across the Vltava from the central city . We probably weren't the only ones challenged by the location because only a handful of an audience attended that afternoon performance. But it was well worth being lost, retracing our way back from a dead end on a muddy

path, lost, confused, constantly referring to the map. The play combined live acting – mainly the contortions of a remarkably acrobatic man in insect-marked tights, whose dialogue was no more than inhuman noises, and two women who made brief pantomime appearances wearing masks. Grainy black and white movie projected scenes of the happenings outside Gregor's room. We had expected a curiosity. Instead, the production moved and disturbed. Perhaps the Joseph K trauma of getting there was essential to the emotional experience.

|

|

In a misapprehension not quite as off base as my Disney delusion, I had assumed Kafka was buried in the Old Jewish Cemetery. But that burial ground, filled to the brim, layer upon layer, with close to 100,000 bodies, was long closed when Kafka died in 1934. It had been in use from 1439 to 1787, Jews forbidden interment outside the ghetto and limited to that small space.

He lies in the family plot in the New Jewish Cemetery, established in 1891, at the corner of two rows, just inside a boundary wall that bears a plaque honoring Max Brod, his lifelong friend, who disobeyed Franz's dying wishes and, to the glory of 20th-century literature, refused to burn the then unpublished manuscripts, saving them from the Nazis in 1939 when he fled to Tel Aviv. The new cemetery is a pleasant place, considering its purpose, spread out over acres, lush with green trees and green vines that climb their trunks and blanket the ground.

|

|

New Jewish Cemetery

New Jewish Cemetery

It's the Old Jewish Cemetery that of all sites in Prague feels the most Kafkaesque, with its centuries of dead piled twelve-deep in caskets one atop the other, the headstones jammed into tight spaces and tumbled every which way. During Kafka's lifetime, the streets of the Jewish quarter replicated the oppressiveness, dark, narrow and winding, a suffocating maze. He wrote of this ghetto, “In us all it still lives – the dark corners, the secret alleys, the shuttered windows, the squalid courtyards, the rowdy pubs, the sinister inns.” Yet, even in his lifetime, in fact, before he reached his teens, the city had begun a program of urban renewal to widen the streets and improve sanitation. Still, those vanished streets permeate his writing, like the settings of Dickens' London and Dostoevsky's St. Petersburg.

Old Jewish Cemetery

Old Jewish Cemetery

Kafka's characters are trapped in the mysterious tangle of this presence, its blind alleys of ambiguity, its haunting unknowns. More than twenty years ago, on the centenary of Kafka's birth in 1983, a year before the 1984 prophesized by George Orwell, I had occasion to compare the world of the two authors:

“Kafka's centenary year, 1983, may be a more significant touchstone of our time than the 1984 of Orwell's dark prophecy. While post-war Western society has measured its political well-being against the potential coming of Big Brother, the literature of the past half century has found its threat to lie inward. Whatever lurks out there is a vast unknown, unnameable; and so, in a world bereft of answers, we have nowhere to turn but within. [. . .] the inner world explored does not yield the rich abundance of Joycean stream-of-consciousness, but rather the wasteland of Kafka's bleak and haunted souls, people with barely remembered pasts, haunted presents, and doubtful futures.

“Through sparse sentences, in sparse claustrophobic settings, isolated, alone, denied communication, these barely named figures grope for meaning without a history to inform them or a culture to sustain them. Clues lead them into literal blind alleys; intellect knots them in conundrums. They are not Winston Smiths fearing totalitarian mind control and a manipulated, imprisoning language. No television cameras need probe their little rooms. Their guilts and anxieties are open secrets. No ministry must contrive doublespeak. Though all the resources of language are available to them, meaning is inaccessible . . .

“Ultimately, Kafka's world is a more terrifying one than Orwell's. In 1984, we know our enemies — sinister technology, thought police, the rat in the cage that breaks our wills. An awful power wants to turn us into mindless automata. But in Kafka, not even sure there is an enemy, we are the rat in the cage; we cannot escape into mindlessness, but are condemned to gnaw at our own hearts, brains, and livers.”

After seeing Prague, I'd like to revise that conclusion. The Trial can be read as prophetic of a historical reality, the fate of the city's Jews under the Nazis. The Old Jewish Cemetery is part of what is called the city's Jewish Museum, not a single building, but a collection of synagogues and sites over several blocks of the old ghetto. To get to the cemetery, you have to pass through the Pincus Synagogue, an empty building whose white walls are covered with the alphabetically listed names of the Czech Jewish Holocaust victims, including three of Kafka's sisters. In a side room are displayed heartbreaking drawings by children in the death camp of Terezin, marvelously imaginative creations from small hands soon to face extermination.

They and their parents and their families – the names on the walls – actualized Joseph K's fictional indictment, the knock on the door in the morning, the accusation against which he cannot defend himself. Unlike Joseph K, they knew their “crime” – racial identity – but as with Joseph K, their assassins wanted them to die “like a dog.” Yet they are named on a wall, commemorated, haunting us with their humanity.

Of course, once you step out from the Pincus Synagogue and walk the few blocks back to the Old Town Square, you're in a different time and a different place, much more likely to see Tinker Bell floating over the spires than Storm Troopers goosestepping down the cobblestones.

[copyright 2005, Walter Cummins]

|