Topic spoke with internationally acclaimed photographer Steve McCurry this summer about the blurred boundary between fact and fantasy. The interview, excerpted in Topic 2: Fantasy, reads in its entirety below.

Can you identify a specific time when you became interested in photography? I started studying film-making in college. I was basically interested in cinema. I took a series of film classes dealing with film criticism and history. At the same time, I took a fine arts photography class in the art department. I started working for the student newspaper, so I was looking at photography from the fine arts angle and also from the journalistic angle, two very different approaches. One is personal – like painting or sculpture; the other is more about storytelling. I started off working on photography from both ends of the spectrum, and then as I started going from film history to film production, I gravitated towards shooting film, towards shooting the production film. I somehow always ended up being the guy doing the stills. So even though I was studying film, it had a very serious photography angle to it. What does photography contribute to our understanding of the world that film doesn't? A still photograph is something which you can always go back to. You can put it on your wall and look at it again and again. Because you can go back to it again and again – because it is that frozen moment – I think it tends to burn in your psyche. It becomes ingrained in your mind. A powerful picture becomes iconic of a place or a time or a situation. When you think back to important times in recent times, probably a lot of what we think of when we conjure up memories of Kennedy, the Roosevelts, or World War II are still pictures. Imagine Kennedy in your mind – you probably come up with a still picture of him. I think that's the power of photography over moving film. No matter how much you love a particular film or video clip, you can't see it unless you turn on the TV or go to the cinema. The power of a picture, whether it's the Mona Lisa or a photograph, is that you can go back to it over and over again. It's always frozen there. Some people believe a photograph can actually help reveal a person's character if the person is photographed at the correct instant. Do you agree with this idea? Yes, I think a still photograph can certainly give insights into a person. I think back to Che Guevera, that one in the garden . . . it says a lot about the man. It shows him as cocky, overconfident. A good portrait is one that says something about the person. We always sort of see ourselves in other people, so a good portrait also says something about the human condition. We see emotions in that person that we can relate to – happiness, sadness, suffering. When a portrait's unsuccessful, it doesn't make you see anything. You need to be moved in some particular direction.

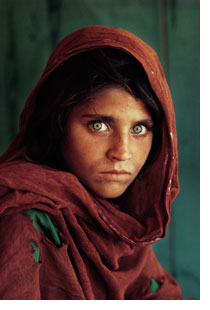

I'm aware that you chose to leave the U.S. and go to India in the late seventies. What caused you to pick that region of the world, and what has continued to draw you back for the purposes of your work? I had already traveled extensively prior to that, but I chose India to launch my freelance career because I'd never been there. I wasn't going to stay for more than two weeks, but I ended up staying for more than two years. It was totally arbitrary, but I think that the thing that continued to lure me was that it's so varied. So much is going on there. Just look at the political situation today. That very small area of Afghanistan and Pakistan are always in the headlines. Next door you have Nepal with the Maoists threatening to take over the country. And then there's Tibet, and there's no more fascinating culture in the world than Tibet. To the south of India, you have Sri Lanka, which is having problems with the Maoist guerillas. It's absolutely rich in terms of culture, religion, politics. I can't think of another part of the world that has so much diversity. Certainly North and South America can't touch it. Do you feel that your work has done a great deal to help westerners better understand these countries? I hope so, in some small way. I treat my subjects with dignity and respect, and I think this helps the public see these people more accurately. I hope that people can appreciate the culture and differences in the way people dress and live and work. It's something that should be celebrated. There's such a rush for homogeneity. Even in the places I visit, I find Chicago Bulls baseball caps and Michael Jackson t-shirts. The people in the villages see it in the magazines, and they want to be cool. They want to be accepted. It's human nature to want to be on the cutting edge – it's the same if you're in Mali, Nepal, or Chicago. Is it difficult to strike a balance between the expectations of the magazine buying public and the lived realities of the places you've photographed? Do people really want to see the reality of the places you go to? I think people generally want to be entertained, not confronted with unpleasantness. Often magazines will try to stay on the sunny side of the street so as not to disturb people. When people grab a magazine off of the newsstand, they don't want to be depressed on the train or bus. How do you identify the correct moment to take a photograph? It's all intuitive and reflexive. You're never sure of the movement because you're always looking and anticipating. You're never sure when the moment is right. You shoot a lot of moments because you never know when the situation will either become peak or evaporate.  Why did the portrait of the Afghan girl so captivate viewers around the world? Why did the portrait of the Afghan girl so captivate viewers around the world?

I think it's that hopeless beauty conveyed in her look. She's a very beautiful girl, but it's clear that she's poor; her face is dirty; her shawl is ripped; yet she has a sort of dignity and perhaps confidence and fortitude. In her eyes, I suppose you could sense that there's something troubling her, something not quite right. Perhaps she's seen more than she should have at such a young age. So she's very pretty, but she has flaws such as her scar and the dirt of her face. It's a mix, which gives it a sort of realness. It's not posed or contrived. It's just a young girl. In the seventeen years between the time you first photographed her and then later went out to look for her again, did you imagine what was going on with her life? We'd had rumors that she'd died, but we had no idea. I imagined she was probably living on the edge of subsistence. We didn't have any real information. The idea of finding her probably seemed like a fantasy to many. What gave you the confidence to go look for her? I got so many letters and emails over the years that I became really determined to try and find her. So many people wanted to know her story. When we found her, we all knew it was her. They wanted to do a scientific check by examining a picture of the iris of her eye against the iris of the original picture, but we all knew it was her. Do you believe that people will be equally enamored with the Afghan girl now that she has an identity, or was her anonymity part of her appeal? I think people's response was to the picture itself, so whether we found her or didn't find her wasn't going to effect how people looked at the picture. Some pictures require a caption to understand the picture, but with his picture, you didn't need one. The picture is strong even without a story. Photographs by Steve McCurry.

Back to Top | More Extras | Subscribe to Topic

|